The German simple past can be virtually ignored if:

You never intend reading a German novel

Get all your news from social media rather than newspapers (online or those actual paper ones)

Live in Southern Germany

Tenses

What are they?

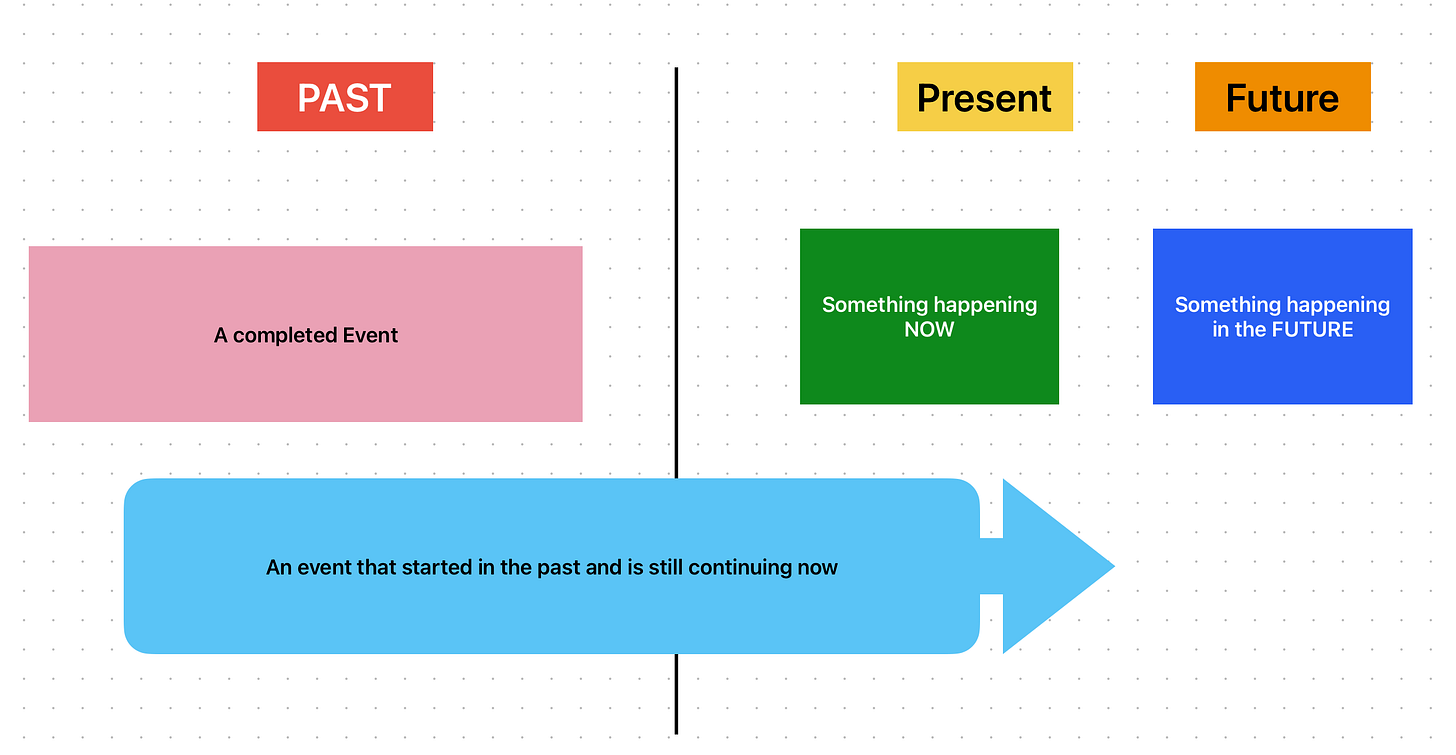

We use tenses to let us know when an action is taking place; to describe its temporal relationship to other actions and events. We have LOTS of them in English and French seems to have a whole stack of them too! Serious grammar aficionados will differentiate between tenses, moods and aspects, but the rest of us don’t really care that much.

In German, we can use the present tense for all sorts of things

things happening now

things that are going to happen in the future

things that started happening in the past and are still happening now

But, we only use the PAST TENSE—whether it’s the simple past or the perfect—if the event or action we are describing is completely in the past.

In most cases, there is no difference in meaning between the Simple Past and the Perfect tense in German.

Simple Past Tense

The simple past tense—as we have noted above—gets use more in Northern Germany than in the South. But it’s still used quite a bit in formal writing: in newspapers and in novels for example where we’re mostly relating what has already happened.

Here, for example, is an excerpt from an *ahem* ‘incredibly famous work’ by an ‘incredibly famous writer’:

Let’s take a look at what is written here. Ignoring the first incomplete sentence, we read

Dunkle Wolken hingen tief über der Stadt.

This is a description of Winter 1994—clearly telling of a day in the past. The verb that indicates this is hingen from the infinitive hängen. In normal usage—ie talking or writing informally about things that hang, or were hanging—we’d just say

Dunkle Wolken haben tief über der Stadt gehangen, OR

Dunkle Wolken sind tief über der Stadt gehangen

…depending mostly on you location in German (ie North vs South). But since this is a piece of formal writing (where also brevity and conciseness is appreciated) we use the simple past. This is an irregular verb which we can tell from the stem change. The verb stem changes from häng_ to hing_. Other irregular verbs undergo different stem changes depending on which vowels are present. We can see this in a later sentence

Mich trieb’s in die Thalia Buchhandlung, ….

Here our verb is treiben =to drive / force / chase. In normal everyday usage, we would write or say

Mich hat’s in die Thalia Buchhandlung getrieben

Some of the other verbs used are regular—which we can see from the typical -te endings:

ein kalter Wind fegte Regen von der Alster her

Wir suchten Zuflucht in den Kaffeehäusern,….

Regular Verbs

The Simple Past tense forms of regular verbs look very similar to the present tense forms, as we can see from the following examples.

Ich suche / Ich suchte

Ich reise / Ich reiste

Ich spiele / ich spielte

Ich kaufe / Ich kaufte

All we’re doing is adding an extra ‘t’. This is more or less the equivalent of the -ed in English (I search / I searched). We do need to take care, however, because we conjugate the verb slightly differently. The 1st person sing. and 3rd person sing. forms are the same.

ich kaufte wir kauften

du kauftest ihr kauftet

er / sie / es kaufte sie/Sie kauften

Some common regular verbs are

Ich sagte (sagen = to say)

Ich spielte (spielen = to play)

Ich wanderte (wandern = to hike / bushwalk)

Ich hörte (hören = to hear / listen to)

Ich liebte (lieben = to love)

Ich arbeitete (arbeiten = to work)

Ich wohnte (wohnen = to live / reside)

Irregular Verbs

The Simple Past tense forms of irregular verbs all undergo a reasonably predictable stem-change such as the ones we noted above. The good thing about German verbs is that most verbs are regular, but the less good thing is that most common verbs are irregular. This means that we need to learn the irregular stem changes, because we can generally not construct them just by adding a -t like we do with the regular verbs. Here’s a short list

These all are fairly easy to use, and we’ll notice that the endings are similar to the ones we have encountered before - BUT notice what happens with the 1st person sing. and the 3rd person sing. forms!

ich sah wir sahen

du sahst ihr saht

er / sie / es sah sie/Sie sahen

We are already familiar with this kind of behaviour from the modal verbs.

Although, we don’t really need to use (unless you’re a reporter or novelist) yourselves, it will be useful to recognise what is happening with these verbs when you encounter them in more formal writing.

But, as we mentioned at the beginning, there are some verbs that we use a lot in everyday speaking and writing—in the simple past

haben

modals

sein

some others

haben

I have vs I had.

That’s the kind of thing that we are reproducing here. Mostly what is going to follow is a noun.

Let’s take a look at how we use the verb haben in the simple past before we check out some examples:

Again, the 1st person sing. and 3rd person sing. forms are the same. Here are some examples:

Ich hatte keine Zeit I had no time.

Ich hatte einen guten Job I had a good job.

Ich hatte gestern Kopfweh I had a headache yesterday

Sometimes, we use the verb haben where we wouldn’t use it in English

Ich hatte Hunger I was hungry

Ich hatte Durst I was thirsty

Ich hatte Angst I was scared

Let’s check out what happens with the modal verbs, because they behave in much the same way:

modal verbs

We’ll no doubt recall that modal verbs also have that peculiarity that the 1st person sing. and 3rd person sing. forms are the same—even in the present tense. Here’s a reminder of the present tense forms and their equivalents in English.

Perhaps you can recognise already that the modal verbs are conjugated much like the verb haben in the simple past tense. Note:

There are no Umlauts in the simple past tense forms

The verb stem does not change otherwise (compared to the infinitive)

The first person sing. and third person sing. forms are the same (see below)

All verbs follow this pattern - we just take the stem of the verb (without the Umlaut) and add on some endings. Here’s the verb müssen

ich musste wir mussten

du musstest ihr musstet

er/sie/es musste sie/Sie mussten

And here’s the verb sollen

ich sollte wir sollten

du solltest ihr solltet

er/sie/es sollte sie/Sie sollten

While we’re at it, here’s mögen (note that the ‘g’ has changed to a ‘ch’ for some strange reason)

ich mochte wir mochten

du mochtest ihr mochtet

er/sie/es mochte sie/Sie mochten

This is the only one of the modal verbs that you mostly won’t be using with another verb.

Let’s turn to the final verb that we want to look at today—the final verb that gets used a lot in everyday writing and speaking in the simple past.

sein

I am vs I was.

That’s the sort of thing we are trying to reproduce here with our verb sein. In the present tense, it’s a very irregular verb, but it gets itself under stricter control in the past tense. Here’s what I mean:

ich war wir waren

du warst ihr wart

er/sie/es war sie/Sie waren

Again, you’ll see that the 1st person sing. and 3rd person sing. forms are the same—and there’s no typical verb ending (no -e or -t).

some others

Whether or not you will use other verbs in the simple past form or not depends on a couple of things:

Where you are in Germany (North vs South)

Personal preference

Generally, people in the North use the simple past tense with more verbs. So you might hear:

Ich hatte Hunger and not Ich habe Hunger gehabt

Ich war in der Stadt and not Ich bin in der Stadt gewesen

Ich musste nach Hause gehen and not Ich habe nach Hause gehen müssen

Er konnte gut Gitarre spielen and not Er hat gut Gitarre spielen können

We know already that these verbs are often used in the simple past, but there are others too that you might hear:

Ich fand das viel zu langweilig (finden)

Es gab ein gutes Restaurant (gehen)

Er wusste es. (wissen)

Er kannte ihn schon (kennen)

Sie las weiter (lesen)

Sie nahm es zurück (zurücknehmen)

And no doubt there are more too.

So, what do we need to know?

How to use the simple past tense forms of sein, haben & the modals

How to recognise the simple past tense of other verbs, particularly if you do any formal reading (newspapers, websites, novels etc)