An Introduction to German Cases

It’s a stereotype about Germans, isn’t it, that they are punctual, efficient, and super organized. Of course, stereotypes are just generalizations, but when it comes to the German language, the "super organized" part definitely applies.

So, if you're learning German, you've probably struggled with all these articles and endings—and maybe at some point, you've come across the idea of CASES.

It might seem like just another hurdle, but really, it's just the German way of keeping things organized—especially NOUNS. And like with any good system of organization, there’s a place for everything, and everything has its place. So, while it might seem overwhelming at first, it’s actually pretty straightforward. But, there’s a lot of confusion about cases, so let me explain first what they do.

First of all, as we know, cases are a way of categorizing the role of nouns and pronouns in a German sentence. Cases help us to determine what’s happening and the identity of the person or thing making it happen. At its most basic a sentence consists of several nouns, or maybe pronouns and at the very least a verb that let’s us know what one or more of those nouns are doing.

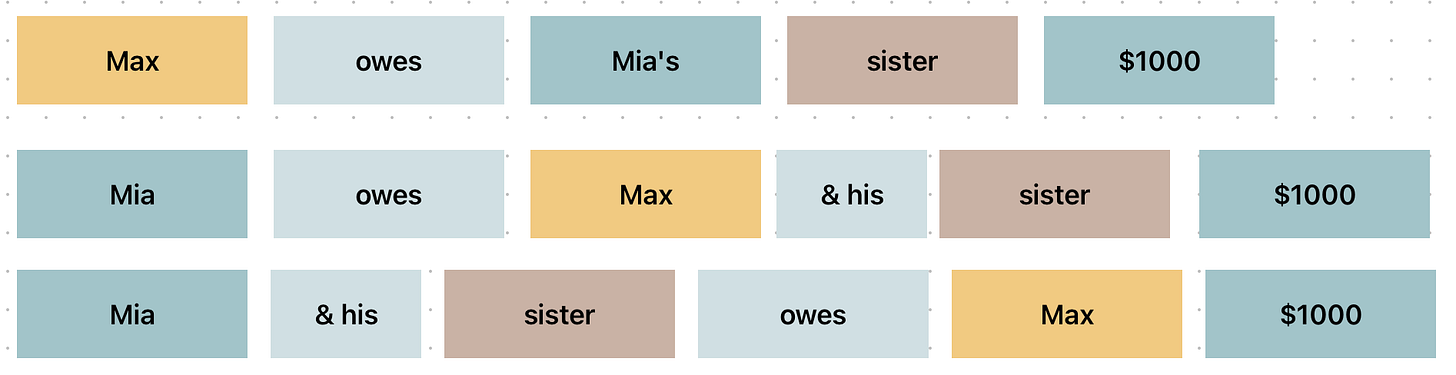

Let me show you in English first. So let’s say we had these four nouns and maybe THIS verb, then I think we’ll all agree it’s important to know which of these four nouns is doing what the verb says.

Is it Max who owes Mia’s sister the $1000? Or is it Mia and her sister who owe Max the money, or maybe some other variation?

And looking at one of these examples more closely, we can see that we have 4 kinds of nouns.

We have the person who owe’s the money—that’s our subject.

We’ve got WHAT they owe — this is the $1000. This is what’s called a direct object. And of course very importantly

there’s the person WHO they owe the money to—this is what’s called an indirect object.

And if we’re indicating that one of these people is the other person’s sister, or brother, then this is a kind of possessive.

So, four kinds of nouns, or four categories. And in German it is exactly the same. It’s as if we had FOUR boxes, or drawers where we could store things—in this situation, we’re storing our Nouns, maybe a bit like this:

We could decide that this first box is where we’re going to keep the subjects. And we know that these are the people or things that do what the verb says they’re doing. So that’s nicely organised already.

And then in the next box we’re going to put any and all of the direct objects (in our previous example, this would be the money, because it’s the money that is owed).

And of course there’s a box for the indirect objects — the people we owe money to, or in other examples, it might be people we send, give, lend, tell or show something to.

That leaves luckily one box which is where all those possessives go. Depending on what we’re talking about, it might be the man’s shoe, the woman’s mother, the dog’s bed, or the skateboard’s wheel.

And all of that would be fine as long as these four kinds of nouns were the only sorts of elements that there might be in a sentence. But before we start talking about that, let’s take a quick look inside the boxes because the Germans don’t just chuck everything into the boxes willy nilly. If we look inside, we’ll see that in most of the boxes there are three little dividers, three places for things to go inside each box.

And I’m sure you’ll know what these are for. German nouns all have genders and there are three genders, so there are three little divisions, so that none of the masculine nouns are getting mixed up with the feminine or the neuter nouns. Which is fine. Except that we also have plural nouns. But only three spots to put things. So the Germans decided they might like to share with the feminine nouns. And the same things happens in our next box, three spots for nouns to go, depending on their gender and the feminine nouns share their spot with the plural nouns.

These are our first two categories, our first two CASES and the first box has the label NOMINATIVE and the second box has the label ACCUSATIVE.

Looking in the next box, we’ll see that there are also three places for us to keep all our nouns nicely organised. But in the meantime, feminine has gotten sick of sharing it’s spot with plural, so we keep them separated. But these only leave the one little spot for all of our masculine nouns AND the neuter nouns. Well now it’s their turn to share. All of those masculine and neuter nouns just have to pile in there together.

This box had the label the dative, so this just leaves us with the last box which if we check is called the genitive. Since this is a box that doesn’t get used that much, there aren’t three places to put things inside, just two. Again, masculine and neuter nouns get on pretty well, so they share this first place, and the feminine and plural are used to hanging out together, so they share the space that’s left over.

So, we’ve got four boxes, labelled the nominative, the accusative, the dative and the genitive, and inside there are some little dividers to keep everything organised. Now, we know where to put our subjects, our direct objects, our indirect objects and any possessives that happen along. And the good thing about all of those little dividers is that they too have labels — do you see that.

In our first box there’s der, das, and die, so we know where to put the masculine and neuter things and also where the feminine and plural things go. And we can see that there are other labels in each of the other boxes — and we’ll see that in each box there are slightly different labels for the gendered nouns.

So maybe at this stage, we're thinking: 'That makes sense! It’s actually a neat and well-organized way to categorize nouns.

The trouble is, there are other elements in sentences that need to be tidied away into these boxes. AND we only have four boxes, so we need to make room for them.

Nominative

The first box — the nominative is probably the easiest. This is where all those subjects go. All those nouns that carry out the action described by the verb. It’s also where the predicate nouns go. So if we had a sentence like

Der Mann ist ein Astronaut

both of these nouns - the man and the astronaut will go into the same box since they’re both the same thing.

Accusative

Our second box, labelled the accusative is where our direct objects go, but we have to make room for a lot of other things too. Like for example the objects of certain prepositions - all of these ones (bis, durch, für, gegen, ohne). So if we had sentences like

Die Frau macht einen Kaffee ohne Milch für ihren Mann.

Only ‘die Frau’ would go into our first box, and each one of the other nouns, Kaffee, Milch and Mann would have to be fitted into the second box, the accusative. But we also have to make room for objects that follow those two-way prepositions when we’re talking about where things are going or being put. So in a sentence like this one:

Das Kind geht ins Badezimmer und wirft den Ball ins Klo

We’ve again only got one subject — it’s the child. And then everything else, the bathroom, the ball and the toilet all need to go into the second box.

Of course, we need to make room for those reflexive pronouns, and even the nouns in phrases like ‘guten Morgen’ since these two are direct objects. They’re what someone is wishing you.

Dative

The third box is labelled the dative and at first this might feel like a junk drawer—lots of things end up here. Yes, we’ve got the indirect objects, but we’ve also got heaps of prepositional objects. Any noun that follows any of these prepositions

aus, außer, bei, mit, nach, seit, von, zu

or even any noun that describes a location that follows any of those two-way prepositions gets stuffed into the drawer. So we might have sentences like these

Die Familie schickt den Freunden in der Schweiz ein Photo von ihrem neuen Haus am Fluss

When we start organising these nouns, only ‘die Familie’ goes into the first box, and then only ‘ein Foto’ goes into the second box, everything else gets piled into the third box - the friends, den Freunden, since they are the indirect object, then der Schweiz and dem Fluss since they are locations and dem Haus too since it is an object that follows the dative preposition ‘von’.

There are some other loose ends that we need to shove into the dative box too. If we have any dative reflexive pronouns - like in the sentence

Der Mann zieht sich einen Pulli an.

Then sich goes into the drawer; and some of the objects of those useful verbs like gefallen, schmecken, gehören and so on, go into our dative box too.

Das Restaurant, das unserem Nachbarn gehört, gefällt meiner Mutter, weil ihr die Nachspeisen dort sehr gut schmecken.

Here we’ve got a few clauses, so any subjects, like das Restaurant and die Nachspeisen go into the first box. The lid of the second box can stay closed, because everything else goes into the dative box. We’ve got our neighbour, dem Nachbarn, the restaurant belongs to him so he’s a dative object. My mother is similarly - in bother clauses - a dative object, since the restaurant appeals to her, because the desserts there taste good to her.

Genitive

This leaves us only really with the last box. And in most informal language, this box will stay closed, so we’ll often have to wipe the cobwebs off, when we need it. It’s used for those possessives we mentioned at the beginning. But only if we say things like

das Ende des Strands

instead of

das Ende von dem Strand

which we might occasionally do, if we want to be a little fancy. But that’s not all that we put into this box. If you’re using nouns after prepositions like

anstatt (or just statt), trotz, während or wegen

then you’re meant to put them into the last box - the genitive box, but lots of people will often just tip them into the dative box instead.

Summary

There are other more complex and less common uses of the genitive, but this might be a good time to quickly review what we’ve learned about cases. They’re like boxes or drawers where we store nouns and pronouns. There are only four boxes, so we have to fit every noun into one of these boxes. In each box there are mostly three little divisions to help us keep the nouns organised. Sometimes nouns with different genders need to share a spot, and other times, feminine nouns needs to share a spot with plural nouns. If you want to take the next step and learn more about cases with lots more German examples, I’d recommend watching this video next.